Orphan Well Gamma Garden

Orphan Well Gamma Garden

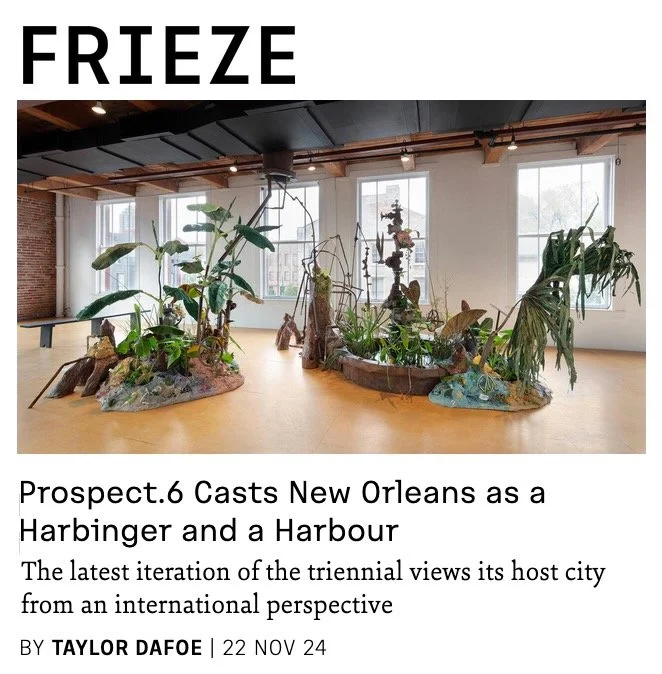

Metal, sugarcane, disposable plastic waste, lime, recycled paint, paper made from sugarcane combined with shredded disposable plastic waste ("plasticane"), ink made from persimmon, goldenrod, indigo, copper and oak galls, pumps, irrigation tubing, diffuser, "fertile rot" scent, living plants, soil, and water

2024

Commissioned for Prospect 6 New Orleans at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans

Video documentation by Varvara Degtiarenko

Essay by Risa Puleo:

Hannah Chalew’s Orphan Well Gamma Garden (OWGG) is a prophetic warning, a materialized vision for a speculative future where ecologies reengineer remnants of the petrochemical industry into conduits for life beyond humans. For her installation, Chalew salvaged an oil wellhead—a machine part that once propelled the extraction of fossil fuels from the wetlands of New Orleans—from a junkyard. At the Contemporary Art Center, this wellhead has been repurposed as a fountain that supports living plants, as well as sculpted ones made from materials that speak to the longer histories of the wetlands’ exploitation.

The New Orleans-based artist and master naturalist looks to the wetlands because climate change’s causes and effects are most visibly entangled there. Oil wells populate the Mississippi River Delta, intermingling with cypress trees in swamps and churning beneath the Gulf Stream. Dredging accelerates erosion in these delicate landscapes, while refining emits greenhouse gases that contribute to the intensity and frequency of hurricanes. In Chalew’s vision for the afterlife of infrastructure, wetland plants embrace their anatomical resemblance to refinery pipes by overtaking and merging with defunct, industrially scaled equipment. Entwined, the formal rhyme between the networks of pipes and root systems of trees suggests mutation.

The title of Chalew’s installation points to two particular phenomena that plague Louisiana’s wetlands. First, when no longer financially viable, wells are abandoned instead of dismantled. The wellhead at the center of Chalew’s installation is one such orphaned object. Often, abandoned equipment left in the environment leaches toxins. When the toxins are radioactive, the wetlands become unofficial gamma gardens, the second phenomenon to which Chalew’s title refers. These atomic-era experiments irradiated plants in order to produce mutations that benefit humans, such as larger, sweeter fruit with longer shelf lives and more abundant crops. In Chalew’s post-human gamma garden, the wetland plants mutate to enhance their resilience against the historical conditions of exploitation by humans.

The development of Louisiana’s wetlands began in the 19th century, when the burgeoning petrochemical industry deemed wetlands to be wastelands. The exploitation of the environment was concurrent with the exploitation of people. Over time, sugarcane plantations became petrochemical refineries. To show how Louisiana’s dual legacies of enslavement and extraction extend into our present, Chalew intervenes in the papermaking process with history-laden materials. The constructed plants in her installation are crafted from “plasticane,” a material Chalew engineers by mixing shredded plastic with bagasse, the fibrous remains left after the sweetness is extruded from sugarcane. The smell of sugar lingers around Orphan Well Gamma Garden: The artist-created fragrance, Fertile Rot, introduces the sweet, fermented scent of oakmoss that conjures the decay of a swamp’s off-gassing. Combined with the subtle sound of hissing that suggests a methane leak, the artist works to update our perceptions of nature with sensory information about the wetlands’ exploitation.

Chalew’s zero-waste and fossil fuel-free philosophy extends beyond sourcing materials from salvage yards. Orphan Well Gamma Garden is powered by a reciprocal community carbon offset project called Maktub Forêt, a restoration effort in the coastal wetland forest near the Mississippi River’s mouth. The living plants in her installation will find a home there after the exhibition closes. Chalew also finds car-free ways to travel and refuses to participate in “artwashing,” the dispersion of money into art institutions that offer oil and gas companies tax breaks and accolades. From the plantation to the refinery to the museum, Chalew’s investigations of the ecological and economic footprint of the petrochemical industry ask us to consider what remains as society increasingly moves away from fossil fuels.

Community Carbon Off-Sets for this Installation:

Chalew worked with the organization Artists Commit to create a climate impact report (CIR) for her installation that tracked the carbon emissions from the materials and their afterlife, production, shipping and energy use of the exhibition. Based on these metrics, she calculated that the carbon cost of OWGG to be 2.5 tons of CO2. She is using her CIR as a guide for a community carbon offset to sequester the carbon emitted as part of her installation which is an essential part of the artwork itself.

For the community carbon offset she is working with Jacqueline Richard and Richie Blink, who are restoring 10.5 acres of former cattle grazing land to coastal wetland forest in Plaquemines Parish, a 1.25 hour drive down the Mississippi River from New Orleans. They call the land they are stewarding Maktub Forêt. Each season, Richard and Blink are raising thousands of cypress seedlings to be planted in the Forêt.

For her carbon off-set project, Chalew invited the public to join her in planting cypress seedlings in the ground. Chalew and a group of nine volunteers planted 110 baby cypress trees in the ground which will offset the 2.5 tons of carbon emissions in 16.6 years. This is a new model for Chalew and its important to her to bring the public in to hold her accountable and also to think together about the carbon costs of our activities and their long-term implications. Just as OWGG envisions the afterlife of the oil and gas industry, planting these trees is a commitment to the afterlife of the installation, as these saplings spend the decade and half plus years growing needed to offset the emissions of my artwork—becoming mature cypress trees and supporting the resilience of our coast.

Exhibition Credits:

Co-Artistic Directors: Miranda Lash + Ebony G Patterson

Exhibition Manager: LB Barfield

Programming Director: Denise Frazier

Exhibition Coordinator: Devin Balara

Exhibition Preparator: Sam Hollier

Production Assistants: Julian Jefferson, Eden Chubb, Maddie Stratton, Ari Chalew

Plumbing + Plant Guidance + Install: Joe Evans and Evans + Lighter Landscape Architecture Plant Donations: CRCL, Louisiana Iris Conservation Initiative

Paint Donations: The Green Project New Orleans

All the friends that donated brown paper bags

Install: Maddie Stratton, Camille Lenain, Aaron, Dom, Eli, Kevin, Sam S.

Venue: Contemporary Art Center New Orleans, Schuyler Williams, Josh Casimier, DiQuan Forcell and all the gallery guards and staff

Maintenance of Installation: Benny Brown

De-Install Crew: Margot, Meredith, Stephen, Ben + Dom

Carbon Offset Land Stewards: Jacqueline Richard + Richie Blink

Tree planting volunteers: Manon Bellet, Margot Herster, Dan Charbonnet, Rebecca Diaz, Halle Parker, Henry

Childcare support: Cypress Atlas, Gail + Stuart Chalew, Lois + Mark Langberg

My family for their endless support: Sam Langberg + Izzy + Lev Langberg-Chalew

Press for Orphan Well Gamma Garden

Mention of my work in Ben Sutton’s The Art Newspaper review of Prospect 6:

“The Baltimore-born, New Orleans-based artist Hannah Chalew & has transformed one of the often forgotten features of Louisiana's landscape, oil and gas infrastructure, into the basis for an indoor fountain. Her installation Orphan Well Gamma Garden (2024) is fashioned from a material she calls "plasticane"-a mix of shredded plastic waste and bagasse, the byproduct of processing sugarcane into juice-and also includes a salvaged oil wellhead, plants native to southern Louisiana and the artist's custom scent, dubbed Fertile Rot, which is based on the odour of the gasses generated by swamps.

The artist has pointedly emblazoned the base of the wellhead with the words "Helis Oil & Gas", a reference to an oil and gas extraction company based in New Orleans whose non-profit arm, the Helis Foundation, is a major funder of the arts in Louisiana (and one of the biggest supporters of this edition of Prospect, though crucially not of Chalew's commission). "Our economy is so entrenched in the oil and gas industries, but so is our culture," Chalew said during a panel last autumn. "They're distracting from what they're doing rather than working to make it better." “

Allison Young mentions my work in her ArtReview review of Prospect 6:

”… Hannah Chalew's sprawling sculptural installation Orphan Well Gamma Garden (2024), at the Contemporary Arts Center, conjoins scavenged pipes, live plants and single-use plastics into a dystopian, posthuman landscape.”

Taylor Dafoe mentions my work in his Frieze review of Prospect 6:

”New Orleans-based artist Hannah Chalew has refashioned an old oil wellhead into a working fountain enlivened by plants – an instrument of extraction turned into a site of regeneration (Orphan Well Gamma Garden, 2024).”